Describing the motorcycle in our story as having a unique lineage would be an understatement. Manufactured by the Lindsay family, who boasted four generations of involvement in the Irish motorcycle industry from the very beginning of the 1900s to the 1990s, this example is the only known survival example of an Irish manufactured motorcycle. The Celtic motorbike was discovered in the 1980s in a farmyard ditch in Ballycommon, County Offaly.

Before we get to how the last surviving Celtic was discovered in Offaly, we bring you back to 1898 when Robert Lindsay opened a small cycle manufacturing business on William Street, Dublin. By 1903 the company was partnered with fellow cycle makers the Robinson brothers from Wandsworth, London with the company now having motorcycles of their own manufacture among the product range.

Robert Lindsay at this time also had workshops at his home in Straffan where it is believed that the first motorcycles were built. It is unclear when the shop’s famous Ship Street location next to Dublin Castle was acquired, however it can be placed on Ship Street from at least 1920.

++

Please support our content creation via www.irelandmade.ie

Just click on the big red SUBSCRIBE button.

++

Lindsay’s was the main agent for numerous motorcycle marques over the decades and in the late 1940s Robert’s grandson Harry Lindsay began to rapidly gain fame as a successful motorcycle racer on road, trials, scrambles and grass track. Harry became famous in motorcycle circles as an importer, dealer, two times Irish land speed record holder and works rider for Vincent motorcycles. We will be covering the life and achievements of Harry Lindsay in a future story.

Robert the founder was originally from Belfast and was an Engineer/electrician. In the late 1800s, he found himself employed by the Barton family in Straffan on a project to electrify Straffan House, now the K-Club golf resort in Kildare and was asked to stay as their estate manager where he remained for his life. In an unusual story, Robert met his future wife, Annie Bolton, after being shot in Waterford while aiding Barton family friends, seeking assistance in a nearby house he met the daughter of the house Annie.

CELTIC ORIGINS

Beginning on William Street in 1898, Robert Lindsay also used the forge and stables at his home on the Barton estate in Kildare as a motorcycle workshop and it is understood that this is where the early motorcycles of The Celtic Cycle Co were crafted. Permanent premises were eventually settled on in Ship Street, Dublin.

While many of the early pioneer motorcycles were just a bicycle with an engine, the Celtic’s frame which was designed and manufactured by Lindsay was a purpose-built motorcycle frame, and one of the very first to use the engine as a stressed member. The machine made almost full use of control cables years before they had become mainstream.

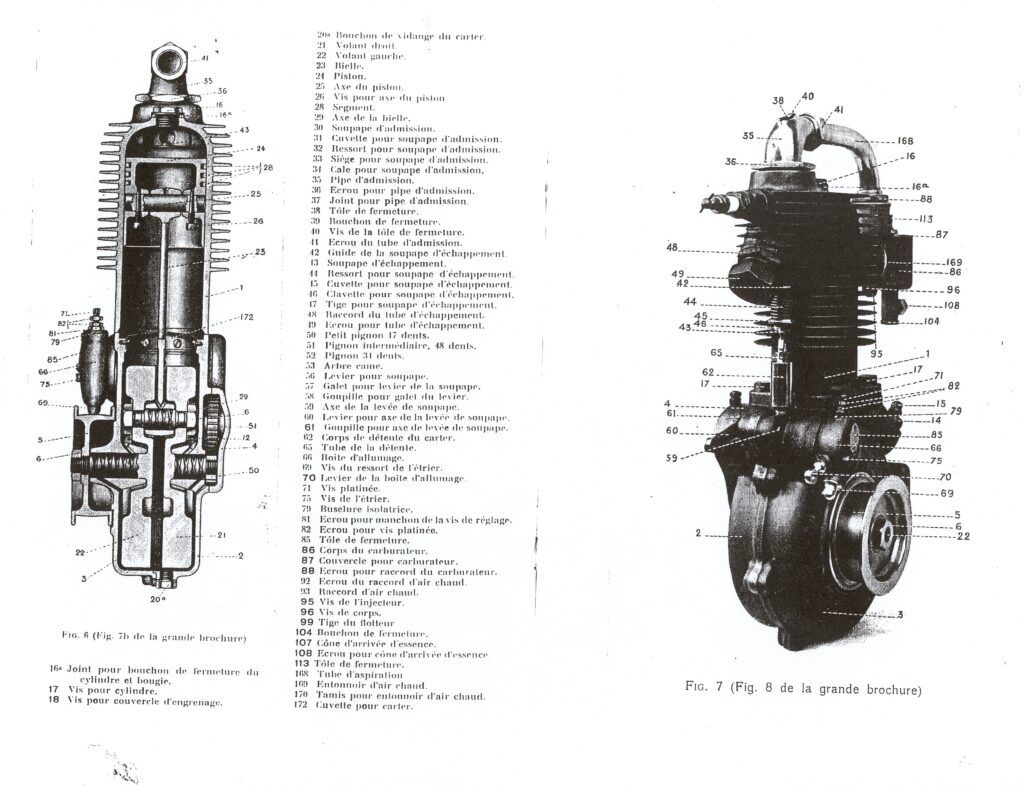

The motor is a 188cc four-stroke single, delivering 2 horsepower, featuring a bore and stroke of 57x74mm, crafted by the Belgian manufacturer Fabrique Nationale. Typical of engines from the time it is an inlet over exhaust configuration with an atmospheric inlet valve. It runs a total loss oiling system with a cast iron piston running in a blind cylinder. For ignition you won’t find a magneto. Power for the spark is provided by limited battery power from a compartment inside the tank.

According to the owner the ignition set up can actually provide an impressive range without recharging as so little current is drawn from the battery. Speed control is managed by advancing or retarding the ignition to control the rpm. With no clutch and direct drive, anytime you need to stop means the engine needs to be cut by raising the exhaust lifter which in turn cuts the engine’s compression. To bring matters to a halt, a leather band brake on the rear hub offers limited braking. The handlebar controls were rudimentary, on the bars the left-hand lever works the exhaust lifter and the right hand lever the rear band brake. While a lever worked by the rider’s right thumb controls the ignition timing.

We have been told that the FN engine was the first designed to be totally operated by Bowden cables instead of the solid linkages which were the norm at the time. This meant that once on the go the only thing you would really need to take your hands off the handlebars for would be to fire the odd shot of oil from the hand operated pump into the engine and to adjust the air valve on the side of the carburettor once up to temperature.

The only suspension on offer is the leather Brooks sprung saddle with the front forks being rigidly braced. Lighting is provided by a single carbide lamp which puts down a surprisingly effective beam of light once properly set up.

WHAT WAS IT LIKE TO RIDE?

Robert Lindsay’s son, James (Jim) Lindsay said that “riding a Celtic was like riding a pneumatic drill” as the engines were badly balanced and gave a lot of vibration.

HISTORY OF THE CELTIC

For Harry Lindsay the origins of the Celtic were of tremendous interest and even though the motorbike had been manufactured by his own family, there were gaps in the story as by the time an interest in Veteran machines took hold, and in the Celtics made by his family, the people involved had long since passed.

Not a lot was known about their London based business partners the Robinson family and their involvement in building the Celtic. The names A Robinson and & J Robinson were known, but it took many years of research and dead ends and eventually via the digitised British 1901 British census the names of Arthur and George Robinson, occupation cycle Makers, were found – from Wandsworth.

Fast forward a few more years and the 1911 census was released. Both brothers were still in the cycle trade and Arthur had married a girl called Jennie, the mystery J Robinson which the family had been aware of for so many years and the registered owner in London of the Kildare registered IO4 bike with a Celtic Motorcycles business address.

However, along the way Harry’s research did throw up other Celtic-related treasure. While in London to search the National Archives in Kew, he placed notices in newspapers, nursing homes and old cycle shops asking if anyone had information on Celtics or the Robinson family. Only one reply was received, and it was a golden nugget! Tom Neape of Brondsbury Park, London posted Harry an old bowed wooden sign engraved with “Celtic Cycle Co Dublin”.

According to Tom the sign came from a cycle shop and Celtic agency on Ladbroke Grove in London named Wilsons. The sign was a perfect match to the style of the brass makers plates on the Celtic itself and the flaking green paint filling the carved letters closely matched the green paint which had been on the Celtic found in the ditch in County Offaly. Tom also reported that in addition to the wooden sign there was also a Celtic mural painted on a wall of the shop prior to it being demolished. However, the whereabouts of Wilsons shop on Ladbroke Grove and when it was demolished, there is no clue.

FINDING THE LAST CELTIC

Only one Celtic motorcycle is known to remain today, discovered in a ditch on a farm in Ballycommon, County Offaly. It’s a c1903 model researched by the current owner as having been originally bought by Bertram H. Barton of Straffan for use by his Scottish gamekeeper James McLeish. This bike was eventually replaced by a second Celtic and James McLeish in later years also had a BSA combination.

Harry Lindsay frequently visited Derick Barton, son of Bertram H. Barton, at Newtown Park nursing home in Dublin and it was Derick who sparked Harry’s pursuit of the surviving frame no47 when Derick recalled where the bike had been sold to in his youth. The hunt was on! Accompanied by friends Joe Cullen and Jack Sutherland, Harry pursued Derick Barton’s lead on the whereabouts of the Celtic in County Offaly. Their investigation led them to the townland Ballycommon and eventually to the farmyard of Bill Dunne who steadfastly claimed there were no motorcycles on his farm.

After a search by the four men in the ditch beside the yard which was full of scrap, a leather saddle was seen sticking out of the briars, and attached to this was the remains of an old motorcycle. Bill Dunne, as Harry recalled, was surprised yet eager to assist. Extracting it from the mud and briars proved difficult, especially as it was connected to two sections of railway sleeper.

Bill Dunne then remembered seeing some brass pieces lying around, which he suspected might have been part of a fuel tank. Bill promptly presented most of a brass tank, which had been partially cut up for metal strips. It fitted the frame perfectly and, to their delight, still bore the stamped brass nameplates reading “Celtic Cycle Co Dublin” on either side. They had found a Celtic motorcycle!

THE RESTORATION

Upon retrieving the Celtic from Offaly and bringing it to his workshop, Harry Lindsay found the bike in dismal shape, having likely spent decades in the ditch and very much showing it. The rear stays were missing, indicating it had been mounted to railway sleepers towards the end of its life, likely for starting the engine and attaching a belt directly to the engine, presumably to power a saw.

Extensive rust had taken its toll, with some frame lugs crumbling at a touch and several tubes badly rotted. The carburettor and ignition were both missing. On its first test run after overhaul Harry Lindsay found the engine to be badly out of balance and the bike didn’t really want to stay in the one spot while idling on the stand. The engine was pulled asunder again and balanced by Harry with great improvement.

In the 1980s, Harry began a thorough restoration. Remarkably, the engine had survived in relatively good condition, partly due to its cast iron construction and partly because early engines were adept at coating themselves in oil, forming a thick protective layer that helped preserve the Fabrique Nationale engine.

The Brooks leather saddle, forks, handlebars, and mudguard mounts underwent restoration. Sufficient remnants of the rotted mudguard remained to match its profile between the stays. The handlebars, in very poor condition, were ground back and replated in their original nickel finish. The bars were deeply pitted and required a generous amount of copper plating to restore the correct thickness and finish to the metal ahead of the final nickel plating.

The brass oil and fuel tank required extensive repairs. Soldering numerous brass pieces to create three separate, completely liquid-tight compartments was a skill that had nearly vanished by the 1980s and is near extinct today.

From previous discussions with his father, Harry Lindsay recalled that the tanks were crafted in Aungier Street, Dublin, by the Cahill family, skilled sheet metal workers with a multi-generational tradition in the trade. Harry located a grandson of the original tank maker, who offered to replicate any wooden model they provided in metal. Well known classic vehicle enthusiast and undertaker Tony Clarke from Blessington fashioned a wooden replica of the damaged tank, which the Cahills then used as a form to resolder the tank into its former glory, preserving the original nameplates and salvaging as many original pieces as possible.

HOW MANY BUILT?

A number of Celtics were registered together in Kildare with the consecutive registration numbers IO3, IO4 and IO5. IO4 appears in the 1907, 1912/13, 1914/15 and 1915/16 registration records as registered to Jennie Robinson, Celtic Cycle Works, Easthill, Wandsworth, more on J Robinson later.

IO5 was registered to Frank E Sparrow an architect with an address of 9 Hume Street, Dublin. Interestingly Sparrow also had a second motorcycle carrying a Dublin City Council registration IK44.

Another estate owner in Kildare, George Mansfield had also owned a Celtic motorcycle, believed to carry Kildare registration IO3 and bought for use by his land steward Mark O’Shea. Mansfield also had another motorcycle carrying registration IO108. The current owner researched the whereabouts of this Celtic was told that in the 1980s Mark O’Shea’s son Mick had gone on to sell IO3 to Jack Cuddihy from Botanic Avenue in Dublin, but this story proved to be a dead end. The enamel front number plate of IO3 was found by a member of the IVVMCC in a pile of scrap on the estate just outside the village of Carragh, County Kildare.

Exhaustive research by the current owner has led to eight machines known to have existed. The Celtic which Harry Lindsay found in Ballycommon had an almost totally obliterated no.47 stamped on the head stock. Were forty-seven motorbikes made? It is hard to say with certainty as factory records have not survived.

The Lindsay motorcycle shop continued trading as a dealership and engineering works until approximately 1990, with three generations managing the business and four generations having worked in it. In 1990 friends of the Lindsay family opened Two Wheel Motorcycles on the site.

Sources of Information and Photo Credit:

Cyber Motorcycles

David P Howard

Kildare Derby Festival Ltd.

Paul Fraser Collectibles

Dillon Family/ National Library of Ireland

David William Glover

++

Please support our content creation via www.irelandmade.ie

Just click on the big red SUBSCRIBE button.

++

Tech Specs

- Celtic Motorcycle specifications:

- Make: Celtic

- Model: c1903 No. 47

- Engine: 188cc four stroke single by Fabrique Nationale - Belgium

- Power: 2hp

- Frame: steel

- Bore and stroke: 57x74mm

- Petrol & oil tank:

- Cahills of Aungier Street – Dublin

- Lubrication: total loss system

- Suspension: Brooks saddle

- Brake: leather band brake on rear hub

- Lighting: single carbide lamp

- Production: Unknown but at least 8 motorcycles are known to have been made in addition to the bicycle end of the business